- “A megalomaniacal, grandiose omnipotence…”

- “…Basically a paranoid schizophrenic who decompensates from time to time.”

- “…The same pathological makeup as Hitler, Castro, Stalin, and other known schizophrenic leaders…”

When thousands of mental health professionals stand up and say things like this about a presidential candidate, it’s reasonable to wonder if there should be a mental fitness standard for politicians. These were among the statements given by psychiatrists and psychologists in 1964 in response to the Republican candidate running against Lyndon Johnson for president.

Barry Goldwater was an Arizona Senator and GOP presidential candidate. He was a staunch fiscal conservative and has been a major influence in defining libertarian philosophies. He believed that the Constitution strictly limited the government’s functions and that any action taken outside of the confines of what was strictly stated therein led down the slippery slope of tyranny. The only things he hated more than Eisenhower’s brand of “Middle Way” Republicans (such as George Romney) were labor unions and Keynesian economic policies. His positions were on the far Right of the party, but after Nixon’s loss to JFK in 1960, Republicans were more welcoming of his anti-New Deal, pro-states’ rights campaign, mirroring his book, The Consistence of a Conservative.

Richard Nixon gave the headline speech at the 1964 Republican Convention. At that same convention, Goldwater’s acceptance speech included his famous line, “Extremism in the defense of liberty is no vice.”

He gained vocal support from the likes of the John Birch Society, Phyllis Schlafly, and Ronald Reagan. Goldwater’s campaign helped jump-start Reagan’s political career, when Reagan delivered his “A Time for Choosing” speech, supporting Goldwater for president.

Goldwater dressed in John Wayne-esque Western wear and touted his Old West roots, emphasizing the romanticized notion that the West was won by men working on their own (ignoring all the federal programs which benefited his family very directly and helped grow his father’s vast wealth). He very proudly stood against everything 1960’s Liberalism stood for: Civil Rights, intellectualism, and idealistic futurism. He railed Soviet Russia, bragging that it would be possible to take an American missile and “lob one into the men’s room at the Kremlin.” He thought dropping a nuke on Vietnam was a step in the right direction. Fears that he would turn the Cold War hot are exemplified in the famous Daisy ad. He swore on the campaign trail, missed meetings with voter groups, and was considered so outside the mainstream that commentators said the only people who would vote for him would be “kooks and nuts.”

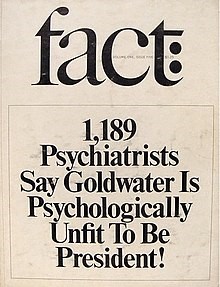

In October 1964 (a month before the election), Fact magazine published the results of a survey sent to over 12000 psychiatrists asking “Do you believe Barry Goldwater is psychologically fit to serve as President of the United States?” About 10% said NO. They published the statements from mental health professionals quoted at the beginning of this post (among many others). Immediately, the American Psychiatric Association (APA) fired back at the magazine, worried about the ethical implications of having psychiatrists diagnose a person whom they have never met.

Barry Goldwater lost the 1964 election to LBJ: the electoral votes were 486 to 52 and LBJ won 61.1% of the popular vote. (Side note: Nixon won 8 years later with a larger margin of electoral college victory: 520 to 17). Though there is little debate that Goldwater would have lost the election without the Fact magazine poll, he sued the magazine’s editor in 1969 and was awarded $75,000.

In response to the Fact magazine poll and subsequent debates, the American Psychiatric Association created a new entry for their Code of Ethics, stating:

On occasion psychiatrists are asked for an opinion about an individual who is in the light of public attention or who has disclosed information about himself/herself through public media. In such circumstances, a psychiatrist may share with the public his or her expertise about psychiatric issues in general. However, it is unethical for a psychiatrist to offer a professional opinion unless he or she has conducted an examination and has been granted proper authorization for such a statement.

Because of its close ties to Barry Goldwater, it is colloquially known as the Goldwater Rule.

The APA has reaffirmed the Goldwater Rule as recently as 2018. The American Psychological Association issued a letter agreeing with this position and the American Medical Association included a similar statement in their code of ethics in 2017. However, not all professional psychiatric organizations agree with the necessity of this ethical rule. The American Psychoanalytic Association (APsaA)told its members, via email, that they were not bound by the rule in 2017.

The Goldwater Rule surfaces in the public awareness at regular intervals, but not just in the political world. The Goldwater Rule is intended to prevent diagnosis of ANY person mental health and medical professionals do not have a therapeutic or diagnostic relationship with. For example, they were also reminded to refrain from providing diagnostic commentary in the wake of the Virginia Tech shooting of 2007.

Goldwater continued writing and speaking about modern conservatism, trying to distance the GOP from the Religious Right, through the 1990’s. He was later diagnosed with and succumbed to Alzheimer’s disease in 1998, at age 89.

Sources and Further Reading

- Kabaservice, G. (2013). Rule and Ruin: The Downfall of Moderation and the Destruction of the Republican Party: From Eisenhower to the Tea Party. Oxford University Press.

- Levin, A. (2016). Goldwater Rule’s origins based on long-ago controversy. Psychiatric News. Retrieved from https://psychnews.psychiatryonline.org/doi/full/10.1176/appi.pn.2016.9a19

- Park S. C. (2018). The Goldwater Rule from the Perspective of Phenomenological Psychopathology. Psychiatry Investigation, 15(2), 102–103. doi:10.30773/pi.2018.01.25

- Perlstein, R. (2009). Before the Storm: Barry Goldwater and the Unmaking of the American Consensus. Bold Type Books.

- Richardson, H. C. (2014). To Make Men Free: A History of the Republican Party. Basic Books.